Black Britannia: The Legendary Congress That Radicalised a Generation

by Bryan Knight

8 September 2020

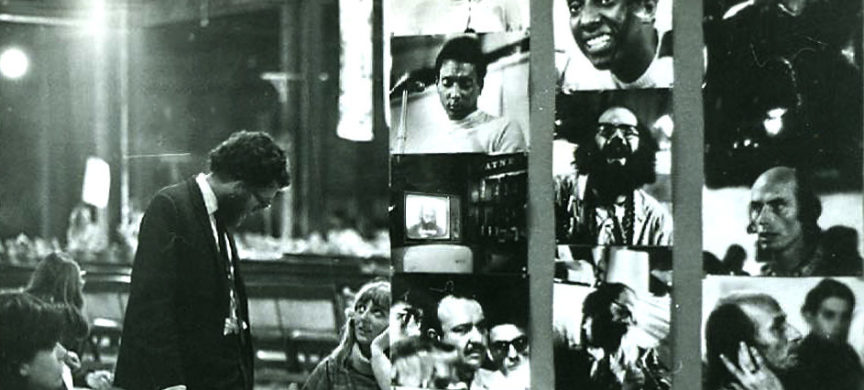

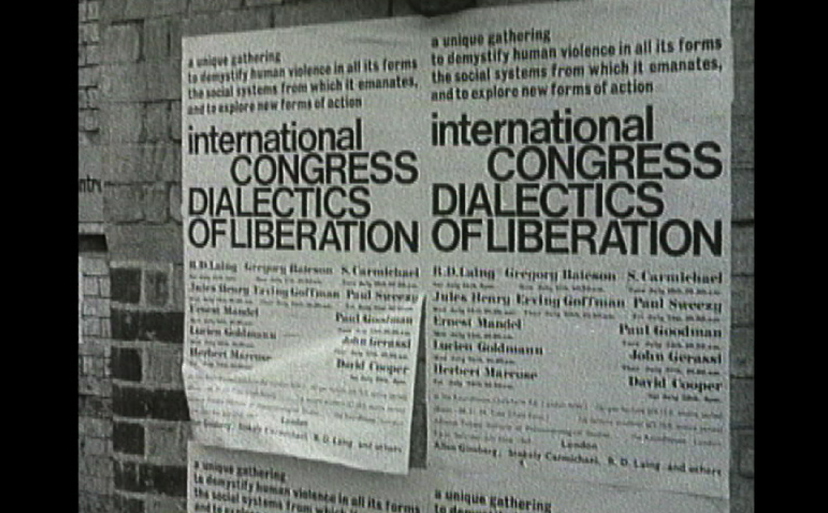

In 1967, the Dialectics of Liberation (for the Demystification of Violence), a now-legendary congress, was held at the Camden Roundhouse in London, bringing together existential psychiatrists, Marxist intellectuals, anarchists and political leaders from around the world to discuss key social issues.

The brainchild of a group of four psychiatrists, all concerned with radical innovation in their field, the congress was organised with the goal of “demystifying human violence in all its forms”. Intending to “bridge the gap between theory and practice”, as stated by organiser and psychiatrist David Cooper, the congress invited boundary-pushing theoreticians and practitioners from across the world to discuss topics such as racism, greed and human instinct.

Over the course of the conference, arguably the most memorable contribution was offered by American Black Power activist Stokely Carmichael. In a series of rousing speeches, Carmchiael advocated for Black Power and called for new ways of fighting individual and institutional racism. His words not only empowered Britain’s Black community but also reimagined the strategy for anti-racist resistance.

The event prompted a turn in the tide for Black British activism, encouraging a heightened militancy in the struggle against racist and capitalist systems of oppression.

Held in response to the Vietnam War, and the mounting global opposition to it, the organisers decided that Britain, having largely refrained from intervening in the conflict, would be an appropriate location to host the event.

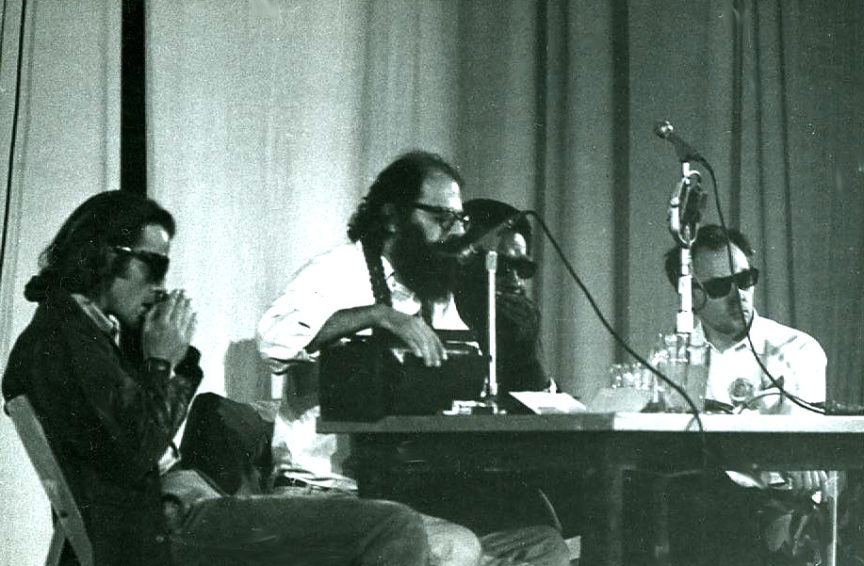

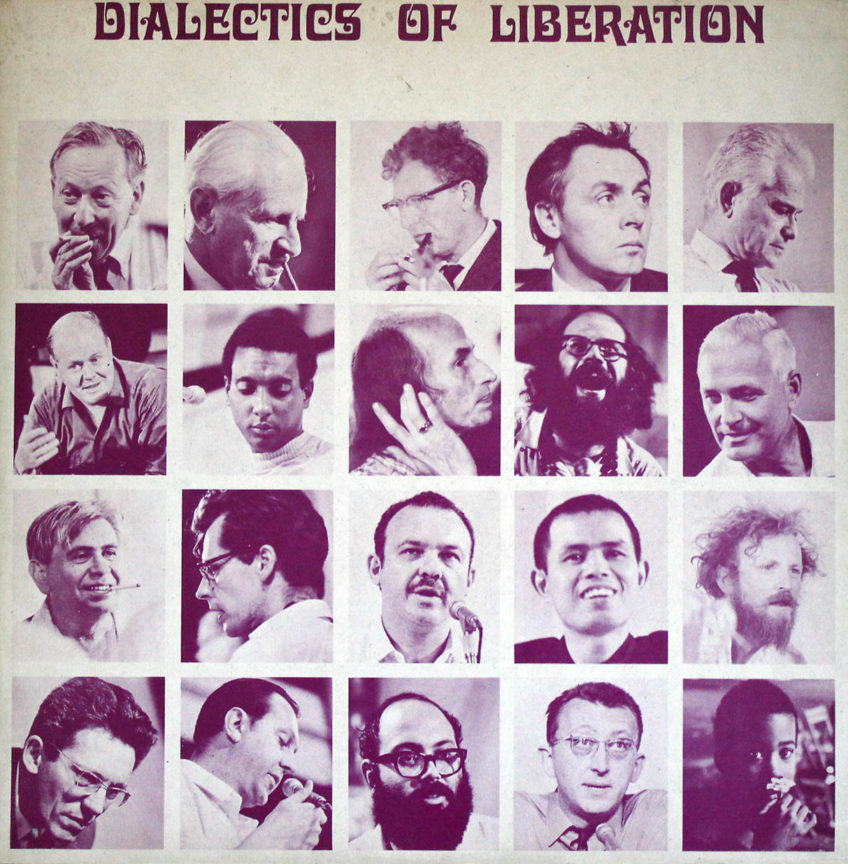

The event line-up was impressive, with Black and white radical thinkers, such as American poet Allen Ginsberg, Scottish psychiatrist R.D. Laing, American journalist Paul Goodman and German philosopher Herbert Marcuse, all convened to speak.

However, while the congress was an internationally inclusive event, featuring delegates from the West Indies and Africa, there was a visible lack of female speakers, with only American visual artist Carolee Schneemann and radical poet Susan Sherman addressing the audience. Later accounts of the congress acknowledged the hostile reception that Schneemann received at the event’s welcoming dinner, which was made worse by her name’s omission from the congress’ posters.

Despite its lacking gender politics, the event demonstrated great radical foresight with regards to climate change. Anthropologist Gregory Bateson was one of the first academics to acknowledge the greenhouse effect and the environmental threats it posed in his congress speech.

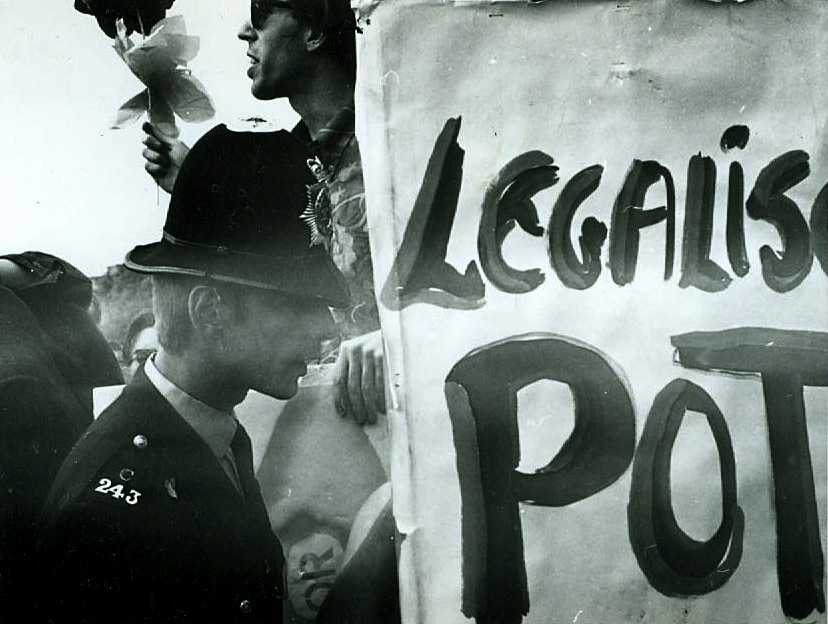

Due to the calibre of its speakers, the event stirred up great excitement amongst radical circles, not just in Britain, but globally. For the British state, however, it inspired great anxiety – particularly given the inclusion of Black radical Carmichael, who was seen as posing a threat to race relations in Britain. Such anxieties had been heightened by explosions of racial tensions in the US, which saw black protestors take to the streets in Newark, New Jersey in opposition to police racism and brutality. Given Carmichael’s stature as a prominent Black Power advocate, the British state, along with the rapt British press, speculated that Carmichael’s visit risked inciting similar clashes at home.

The congress was convened during a tense moment for British race relations. Black and white working-class communities were still dealing with the aftermath of the 1958 riots in Nottingham and Notting Hill, which saw black migrants attacked by local white youths against a backdrop of economic turmoil and racial intolerance. Meanwhile, the racist murder of Black Antiguan expatriate Kelso Cochrane in 1959, coupled with the Parliamentary debates over immigration restrictions merely exacerbated racial tensions in Britain.

Against this increasingly antagonistic backdrop, the 1964 UK general election saw politicians increasingly adopting anti-immigrant rhetoric and ideas after seeing how politically lucrative such a stance could be.

In what was described by then Labour prime minister Harold Wilson as an “utterly squalid” campaign, Conservative hopeful Peter Griffiths’ ran on a platform designed to exploit working-class grievances, using racist tactics such as the adoption of the slogan: “If you want a N*gger neighbour, vote Labour”. Despite Labour being expected to hold the seat, Griffith’s appeal to anti-immigrant sentiment in a county borough that had the highest percentage of recent immigrants to England, resulted in the party winning on a seven percent swing.

Griffith’s victory encouraged politicians from both parties to embrace similarly racist views, most notably Conservative MP Enoch Powell, who previously oversaw a campaign to recruit Commonwealth migrants as health workers before drastically shifting towards an anti-immigration stance, resulting in his infamous ‘Rivers of Blood’ speech four years later.

It was in this context that Carmichael and his Black British followers spoke out, demanding radical change.

Carmichael, like his fellow African American activists, was aware of the grievances of Britain’s Black community and used his visit as an opportunity to engage with academics and activists alike.

Arriving in Britain on 15 July, for an 11-day speaking tour, Carmichael met with London’s Black community to talk about the state of race relations in Britain, whilst being guided through the city by Black activist Michael de Freitas. As well as making sure to visit Black intellectuals such as C. L. R. James, Carmichael also connected with grassroots communities through his speeches at Speaker’s Corner and London’s West Indian Students’ Centre.

Speaking on three different occasions over the course of the congress, Carmichael used the opportunity to define Black Power, condemn Western imperialism and seek the solidarity of Black communities around the world. Documentarian Peter Davis, who attended the event, recalled Carmichael’s tactical use of “intonations learned in the black churches in America” – a technique which held the audience in rapture.

Carmichael began by exposing the “biggest lies” propagated by the West, citing Christopher Columbus’ ‘discovery’ of the Americas and the supremacy of ‘Western Civilisation’, as examples. He went on to condemn the integrationist politics of the West, arguing that integration involved Black people accommodating white society, which was “absolutely absurd unless [it was a two-way street]”. Invoking Frederick Douglas, he described integrationists as “want[ing] rain without thunder” and clarified that “power concedes nothing without demands”.

Instead, Carmichael advocated for Black Power which, he argued, initiated a diversion away from ineffective integrationist politics towards longer-lasting radical change. Against a backdrop of increasing economic inequality, Carmichael also disputed the effectiveness of Black capitalism, arguing that racism and capitalism “seem to go hand-in-hand” as a result of unequal wealth distribution.

In fighting such systems of oppression, Carmichael drew on the international scope of the congress to stress the importance of Black globality. In order to destroy the Black community’s “minority complex” and enable them to see themselves as part of a global majority, he told the audience that “we have to extend the fight internationally”.

Carmichael’s rousing speeches had a profound impact on the 500 to 1000 people who attended the congress. Women’s rights campaigner Selma James recalls how Carmichael’s words “woke people up.” Similarly, recounting the experience in her autobiography, African American radical Angela Davis wrote:

“In the enormous barn-like structure, its floor covered with sawdust, the air reeked heavily of marijuana, and there were rumors that one speaker, a psychologist, was high on acid. […] As I listened to Stokely’s words, cutting like a switchblade, accusing the enemy as I had never heard before, I admit that I felt the cathartic power of his speech.”

Although Black British resistance was happening before the congress – for example lobbying organisations such as the Campaign Against Racial Discrimination (CARD) – Carmichael’s presence undeniably electrified Black activism in Britain and redefined the objectives of anti-racist organising.

His visit coincided with a “deepening crisis among black activists”, who debated whether to go down a measured reformist path – as seen with CARD – or champion radicalism. Marion Glean, an early member of CARD articulated these debates and noted the splintering between those who embodied the anti-racist “legalistic bourgeoisie” and radicals rooted firmly at the grassroots.

Carmichael called for an intensification of black activism and encouraged the creation of black power organisations. The impact of Carmichael’s words would later be seen in the emergence of groups such as the British Black Panther Movement and Black Unity and Freedom party.

As historian Rob Waters argues, Carmichael redefined Blackness as being “revolutionary, anticolonial and resolutely confrontational” in its resistance to racism. His speeches were a call to action for black people in Britain, prompting the community to heighten the militancy in their actions and demands.

But despite Carmichael’s impact – or rather, because of it – the paranoia of the British state prevailed. In the days following Carmichael’s appearances at the congress, he was allegedly visited by Special Branch agents and asked to leave the country – a request to which he quickly complied. Shortly after the Special Branch’s visit, Home Secretary Roy Jenkins announced a ban, preventing Carmichael from re-entering the country.

Despite Carmichael being unable to return to Britain, the seeds of dissent had already been planted. In the aftermath of the congress, Black Power organising exploded in the UK, resulting in the formation of numerous explicitly Black radical organisations. Activists such as De Freitas, Egbuna and Roy Sawh rose in prominence and popularity due to their association with Carmichael. Radical resistance in Britain took its shape and anti-racist organisations began challenging British racism using Black Power principles in their grassroots action.

Through his now-legendary speeches, Carmichael has had a lasting effect on Black radical organising in Britain, redefining the criterion of resistance, popularising radical anti-racist politics and inspiring the Black community to action. His argument for situating Black struggles in a global context also has a powerful legacy and is in part to thank for British Black Radicalism’s unique focus on international issues such as colonialism. While his rejection of reformist politics, he also served to bolster radical sections of the grassroots, pushing the discourse leftward.

Looking back on his experience at the congress, Peter Davis considers the event’s “great theme” to be that of the “imbalance between ‘accepted’ violence (‘law-and-order’) […and the] protests of those who oppose institutionalized injustice”. The event’s wide-ranging discussion of issues from race relations to police brutality to the environment, are, according to Davis, topics which “resonate even more strongly today”.

The first of its kind, the congress was unprecedented in its bringing together of academics and activists involved in direct political confrontation from around the world to unpack the most pressing issues of the day.

And with the topics discussed – racism, economic inequality and climate change – just as relevant today as they were then (in some cases even more so), current progressives would do well to take inspiration from their forebears in creating boundary-pushing, international spaces, which allow open, critical, movement-inspiring dialogues to flourish.

Bryan Knight is an oral historian and journalist based in London. He hosts the Tell A Friend podcast, discussing current affairs and historical topics.

This article is the fifth and final instalment in Black Britannia, a series which reflects on the country’s Black radical history.

Part one is here: Today’s Anti-Racist Movement Must Remember Britain’s Black Radical History.

Part two is here: There is a Long, Racist History of State Surveillance of Black Communities.

Part three is here: The Race Today Collective Demonstrated the Radical Potential of Journalism.

Part four is here: The Asian Youth Movements That Demonstrated the Potential of Anti-Racist Solidarity.