Filth: Single-Use Plastics Tell a Story of Capitalist Greed and Planetary Catastrophe

by Eleanor Penny

19 June 2020

It was 1997, and yachtsman Charles Moore was trying to get home. His boat was cutting a line through the chasms of Pacific water stretching from Hawaii east to California, when the sea around him began to thicken with bottles, with fishnets, miles of plastic flotsam stretching as far as the eye can see. That was the first recorded discovery of the ‘Great Pacific Garbage Patch’, an area twice the size of Texas where the pounding gyres of ocean current reel in the tonnes of undying plastic trash washed every day from the land into the sea. More exactly, it’s known as the Eastern Garbage Patch – mirrored thousands of miles away by a Western Garbage Patch, collecting in the waters off the coast of Japan.

For years, scientists tracking the progress of plastic detritus through the ocean had speculated on the existence of a giant stewpot of marine debris. Serendipity delivered. In 1990, a shipment of Nike Trainers was lost overboard. Two years later, the container ship Evergreen Ever Laurel accidentally tipped 288,000 rubber ducks into the sea. Then they were 34,000 ice hockey gloves. By mapping the drift of ducks and gloves and other detritus across the waves, scientists mapped more accurately the ocean currents sucking trash into huge vortices. They concluded that much of what we send into the ocean will never return to shore.

Plastics are a miracle, singular stroke of human ingenuity. Cheap, abundant availability of strong, flexible, polymers has allowed us to somersault breezily over the limitations of the found environment – replacing metal, rock and plant-based materials in every imaginable industry. They have helped take us into outer space, thresh the boundaries of medicine, stoke successive revolutions of digital technology. But where human ingenuity meets the profit function, the planet usually counts the cost.

During the second world war, limited supplies of raw materials led to an explosion of plastics manufacturing and research – increasingly by 300% in the US alone. As post-war western economies boomed, and consumer capitalism took flight, so consumer goods markets relied more and more heavily on plastics throughout the process of production, transportation, storage and marketing. The plastics revolution wove through a consumer-capitalist revolution thriving on principles of disposability, portability and obsolescence; that in order to satiate the growth-orientated profit drives of ascendant capitalism, goods must be bought, thrown away, bought again, produced more cheaply and in greater quantities for a dwindling life-expectancy in the hands of users and an epochal existence on the ocean floor. Oil-dependent, it was bound to and bolstered the dominance of the fossil fuel industry. Even as the environmental toll reared its head through the sixties and seventies, corporations cut sweetheart backroom deals and free trade get-out clauses to ensure no costly-cleanup operation would cut short profit margins.

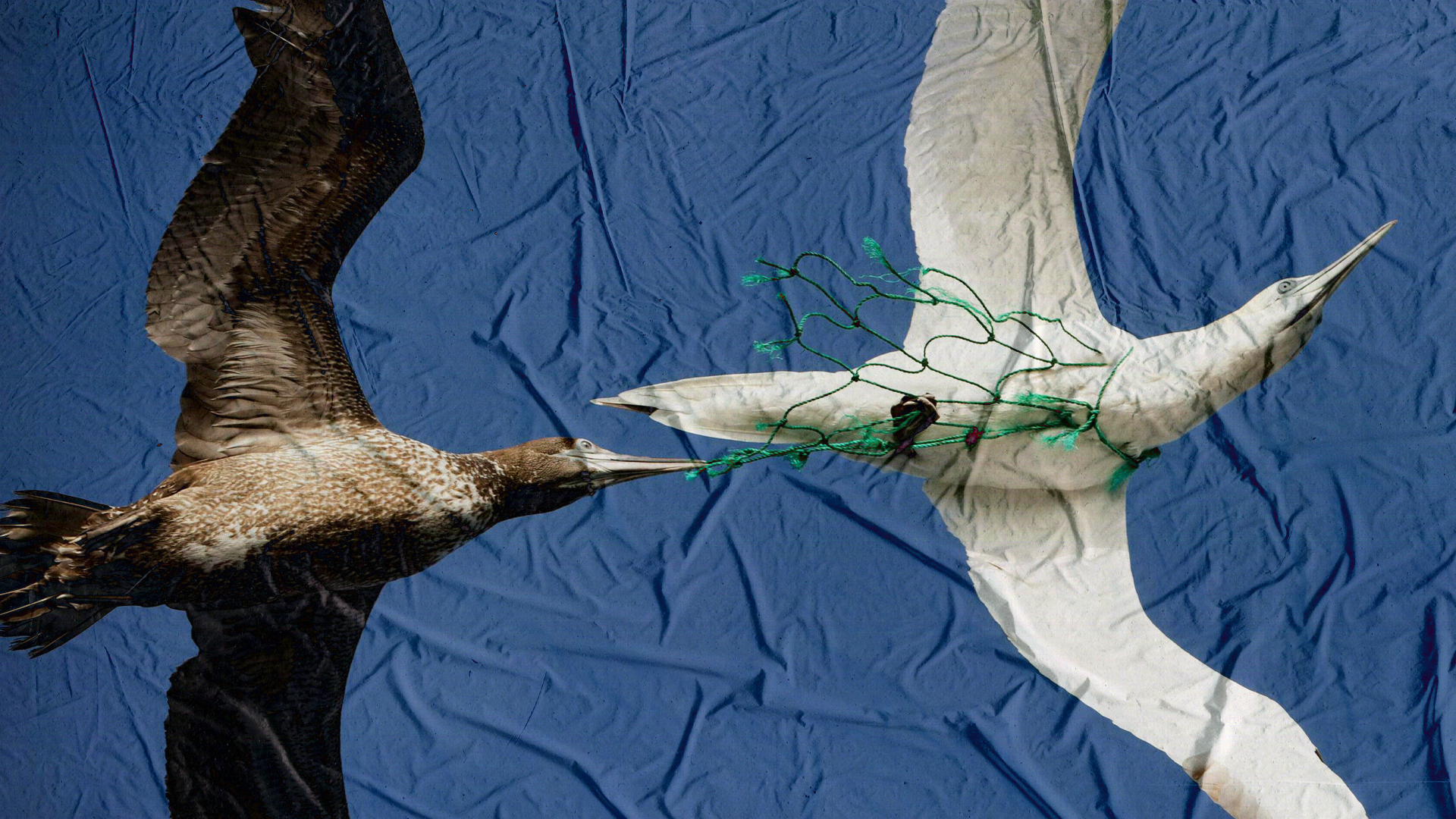

The ocean garbage welts are more soup than landmass – mostly a smog of fragments and particulates. Plastics can erode into vanishingly small microparticles – harder to trace, harder to recover – but they were built to resist the temptations of rot and decay, and do so with tragic mastery. They have already outlived several brief human generations.

Not everything floats to the surface of the patches. Many common household plastics are denser than water – collecting on the ocean bed. Plastics have been found in the stomachs of deep-water life, of fish that have never known sunlight. It is predicted that by 2050, the weight of plastic in the ocean will be greater than the weight of fish. Put otherwise – 90% of planetary life is in the oceans, and in thirty years it is set to be rivalled by waste.

As they erode, plastics can leech out toxic chemicals. Their microparticles contaminate food and water supplies for larger animals – humans among them. Rushing through the blood of the average human, you will find invisible specks of plastic. Meanwhile, plastics weaken the ability of the sea to absorb CO2 – exacerbating global warming.

‘Away’ is a tricky term. We always throw things somewhere – but for larger economies, both the oceans and the poorer economies of the global south are far enough ‘away’ to be somewhere out of sight and out of mind, where the distasteful underbelly of profit-making is someone else’s problem. Domestic recycling infrastructure and an emphasis on circular production are onerous, whereas faraway waste dumps offer political convenience and shareholder comfort.

So plastic waste often traces a route back along neocolonial axes of plunder, extraction and trade domination – piling up in poorer countries where it can wreak havoc on the health of residents. Plumes of toxic smoke from plastic infernos blow over residential buildings. Slews clog up water supplies, filth mountains harbour infectious diseases, mismanaged dumps encroach on agricultural land and contaminate fishing waters. During recent transnational attempts to stop Southeast Asian countries being overwhelmed by non-recyclable waste, some negotiators – notably from the US – complained that binding agreements on waste disposal might stifle business with the cost and responsibility for the by-products of their profit-making.

That is to say that the story of single-use plastics is a story of an economic system driven to short-term private wealth hoarding at long-term public cost, loyal to the watchwords of fossil-dependency and over-consumption, where lawmakers collude to loosen any restraining binds of corporate accountability. It is the story of planetary catastrophe.

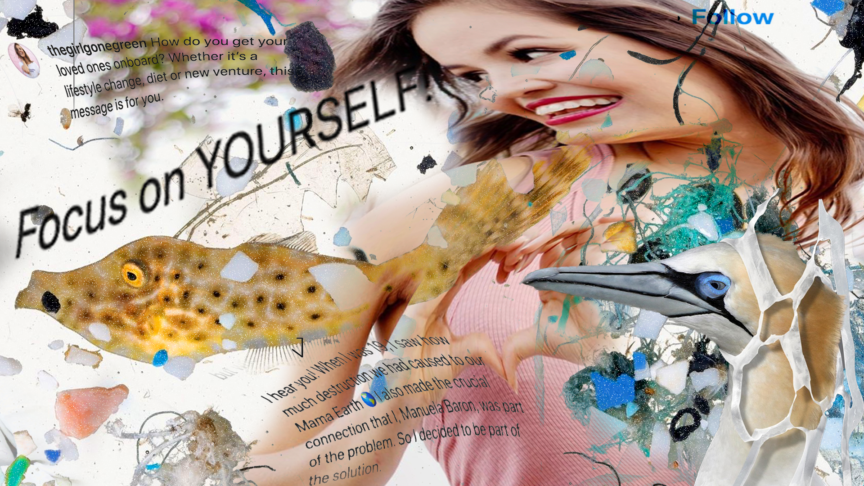

Recent years have seen a flurry of legislative fuss over totemic throwaways; seeing single-use plastic straws and microbeads banned in a splash of press as governments tout their green credentials to an increasingly eco-anxious electorate. Meanwhile, those searching for ways to lighten their own carbon footprint will find no end of advice to cut back on single-use plastics; ditch the plastic toothbrushes, carry a water bottle, buy unpackaged groceries. Do your bit. All helpful suggestions. But we’d do well to meet with scepticism full-throated lawmaker enthusiasm for consumer responsibility and demand-side action as the first and last word on climate politics – often used as a flimsy placebo for meaningful action, diverting attention from government intransigence and masking the operation of economic power. It is a prism through which a critique of political power warps into a short-termist consumer blame game. The hollow politics of plastic too-often individualise the task of saving the planet, drain it of political content as public institutions continue to sponsor ecocide disaster.

Gestural bans train their sights on specific goods – usually easily subbed in for replacements which are no guarantor of climate salvation. McDonald’s new generation of paper straws has a greater carbon footprint than their plastic forebears, using wood razored in vast swathes from the planet’s green lungs. Recent EU legislation bans single-use plastics only where “alternatives are easily available and affordable” – a light slap on the wrist to pollutant industries which fails to take production-chains to task for their wholesale environmental impact, and leaves the fatal ethic of inbuilt obsolescence untouched.

The vogue for green consumerism opens up charming new avenues for canny marketers, targeting a largely middle-class market with promises to ditch the plastic in favour of ‘all natural’ materials which, well, just feel more wholesome and conscientious. But likewise, leagues of alternatives like bamboo exact a heavy carbon toll glossed by their eco-friendly flair. Indeed, biodegradable plastics threaten to worsen pollution, lulling us into a false sense of sustainability as we release them into the world, without the infrastructure to ensure they break down properly. They have many similar health risks to their durable cousins and also use up resources at a rate our planet cannot tolerate.

Ad-hoc consumer switch-outs and opt-outs let businesses and governments flog us the sensation of change within the stubborn structures of disaster. Over the last decade, the UK government has subsided the fossil fuel industry to the tune of over ten billion pounds. Over the last months, it has merrily handed over further billions to bailout failing airlines – no strings attached. Plastic straws though, you know?

The sensation of change often comes with a heavy price tag which puts it out of the range of lower-income consumers, an easy sop to those keen to drive a wedge deeper between climate politics and class politics; as planetary salvation is rested not, say, on a radical working-class movement, but on the enlightened shopping patterns of those with the false luxury of choosing between different flavours of CO2. (We should mention that middle-class consumers are reliably the source of more carbon emissions than their working-class counterparts, regardless of ecological commitments. In the questions of personal carbon footprint, how much you buy often trumps what.)

We should perhaps not be surprised that these are the withered solutions available to the addled imaginations of market loyalists, lashed to the mast of demand-side economics on a ship careering right into the rocks. They are, by necessity, blood-loyal to the dogma idea that consumer choice is the fundamental force in the economy – the force of humanitarian enlightenment and final jury of economic success, the only acceptable lever of power over the market, the authentic zone of politics. But the reality is that the global dominance of single-use plastics is less about consumer demand and more a matter of corporate convenience and polluter impunity embedded into production chains from the mine to the scrapheap. The green pound alone opens up only the smallest, most shrivelled zone of political possibility in which we occasionally, individually opt-out of a single link in the economic chain. The public foots the bill, the planet bears the cost, and the private individual shoulders the blame for his fatal choice of toothbrush.

All of this, of course, cleaves nicely to the capitalist mythology that the planetary crisis we face is a problem of human hubris – the final tragic showdown of a parasitic species doomed to destroy any ecosystem unfortunate enough to play host to it. That the problem is individual humans and their behaviours – rather than a problem of political power, a problem of an incidental, contingent way in which powerful economic forces have arranged humanity’s relationship to the rest of the web of life. Very nice, very tidy if you’re determined to avoid at all costs the idea that the survival of our life support systems depends on an urgent reckoning with polluter power and its political enablers everywhere.

Eleanor Penny is a writer and a regular contributor to Novara Media.

This article is the sixth instalment in her series on the political economy of things we consider to be waste, rubbish, junk – or filth.

Part one is here: Trans Bathroom Panics May Be New, but Public Toilets Have Always Been a Political Battleground

Part two is here: Racist Scaremongering Around Covid-19 Is Nothing New. We Have Always Blamed Racial Others for Disease

Part three is here: Space Junk Is Always Somebody Else’s Problem – But Eventually Someone Is Going to Have to Clean It Up

Part four is here: Coronavirus Has Shown That Cleaners Are Essential, but Labelling Them ‘Low-Skilled’ Legitimises Exploitation

Part five is here: Disease, Drugs or Looting – Brutal Policing is Always Framed As Protecting ‘the Public’ From Infection