Filth: Food Safety Regulations Are Not Just ‘Red Tape’. They Exist to Protect People Over Profit

by Eleanor Penny

10 July 2020

Red tape gets a bad rap. In recent years it has earned a dubious reputation as a catch-all for the stultifying obsessions of jobsworth bureaucrats, the far-off European elites determined to smother earnest British enterprises at first gasp with layers of silly regulation about banana curvature and pie provenance.

During the Brexit referendum, neo-conservative, Atlanticist wet dreams of predatory, unregulated business took pride of place in the culture war. Zombie rumours about the censorious, trivial priorities of EU red tape stalked social media. The rightwing press urged the voting public to hack away at the choking cords of EU regulation and consumer safety standards to finally unleash business. They did not say on whom. With food safety regulations now on the chopping block marked Brexit, it’s time to worry about what else might be served up alongside dinner.

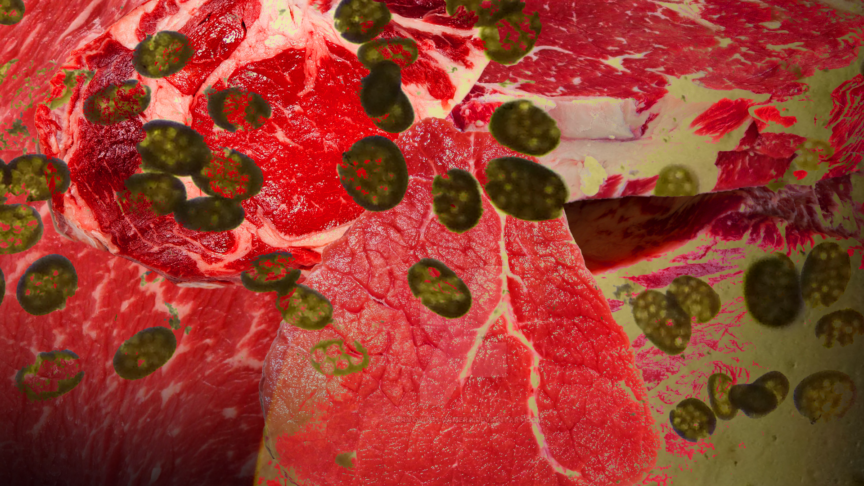

The food business is necessarily filthy, sorting the edible from the excrement, the dirt, the bugs, the chemicals and the run-off of mass food production, in the hopes it will be delivered into our bodies in a somewhat safe condition. Every mealtime is an act of enormous hope and trust in a social contract that is nominally supposed to guarantee that businesses can’t flog us fatal slices of chicken or peaches packed in botulism. The problem comes when the people selling the food and those consuming it have rather different standards of success – and for those producing it, limited ways of containing the transmission of disease.

We’ve always had to tangle with some much-warranted anxieties over food safety, and the disease and contamination that can easily pass on to our plates. UK food safety laws stretch all the way back to the 12th century, when haphazard attempts at regulating beer and bread were charged to early courts which regularly tested the quality of beer by seeing how firmly it stuck your trousers to a bench.

Georgian-era bakers in Britain were known to pad out their flour with alum, chalk, lime and ground bones to pass it off as the more expensive white flour usually reserved for the wealthy. Parliament banned the practice – but it went largely unenforced and ignored.

As the industrial revolution ground into gear, public health scares around food redoubled, as large-scale production in plants with little sanitation, worked on by people with little healthcare and few safety measures, helped spread campylobacter, salmonella, typhoid, and tuberculosis.

Industrial managers in the 18th century fumed at worker absenteeism caused by adulterated food – and through the late 1800s and early 1900s, legislation struggled to keep up with new chimerical ways to spread foodborne illness. Upton Sinclair’s 1905 muckraking novel The Jungle detailed the horrific conditions in Chicago meatpacking districts, the resulting uproar ushering in new legislation – although, Sinclair noted this was “not because the public cared anything about the [migrant] workers, but simply because the public did not want to eat tubercular beef”.

Still, we stumble from outbreak to outrage to retroactive patch-and-stitch legislation as lawmakers are haltingly forced to keep up with intensive agribusiness, where cost-saving measures of dubious safety are coupled with cramped, unhygienic and exploitative conditions for workers.

The 1990s saw UK-wide cases of variant Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, commonly known as ‘Mad Cow Disease’ for the nasty effects of a syndrome which slowly, fatally, eats away at the brain and spinal cord of its host. It is thought to be spread by feeding ground-up cattle to younger calves in the form of meat-and-bone-meal. The practice is now banned. But irresponsible agribusiness is still credited with many more zoonoses leaping from animal hosts to human populations with no previous immunity. Covid-19 among them.

The cost-effective ways of solving the problem of foodborne disease are not always the best; hence, for instance, the much-debated tactic of chlorine-washing chicken meat to kill bacteria. Experts disagree on the extent to which the chlorine itself is a problem, but few deny that this is a blunt instrument to solve the problem of how easily disease spreads in the gruesome battery farming conditions that US regulation allows. The US, where the practice is commonplace, has vastly higher rates of food poisoning.

In the profit margins playoff, businesses ask themselves how many food poisonings are an acceptable PR price to pay for practices which cut corners on hygiene for long-term company pay-off. In a multi-billion dollar industry, these aren’t petty questions – and genuinely robust food safety practices can carve a hefty chunk out of profits. A price many people will go to great lengths not to pay.

This is where food safety regulations are supposed to come in. They stress test our institutions’ readiness and capacity to protect people over profit, as a minimal baseline restraint to try to make sure business practices avoid poisoning the people off whom they’re making their dough, or contaminating the water supplies with slurry and spill-off. They can act as a guarantee of protection to those without the cash to spend on pricier organics and farm-to-table ingredients, and a frontier of corporate accountability, where national and transnational institutions can help tip the balance of power and information in favour of consumers and employees.

The spectre of red tape haunting Europe is not some socialist menace, or indeed, depending on your personal predilections, a socialist utopia. Food safety regulations are favoured by some businesses as a proxy for public trust in their brands – and also a helpful backstop against litigation if they can prove they’ve followed reasonable steps to meet guidelines.

Europe has a distinctly patchy record on consumer protections and business accountability – often bending to the demands of agribusiness, and favouring consumer-end protections over workplace protections (eg you can smoke out your staff with toxic chemicals, as long as they don’t end up soaking into the market product). But as a guarantor of basic consumer safety, they are a country mile ahead of that which await us in a Trump-deal Brexit, which threatens to hollow out safety standards to ‘harmonise’ UK regulation with its more lax Atlantic partners, who have a tendency to prioritise business sense over biology.

Industry professionals, NGOs and consumer watchdogs have warned of the dangers; food contaminated with rat hairs, insect fragments and faecal matter are all permissible under US food safety legislation, as are 72 pesticides all currently banned in the UK. The US has no specific regulation for baby food; recent tests found that 95% contained toxic metals, with 73% containing traces of arsenic. Meat farming makes weapons-grade use of antibiotics to combat the risk of infection – stoking up the risks of mass antibiotic resistance. And in preliminary negotiations, the US has driven home the fact that any deal it signs must give ground on food regulations, to ensure “greater regulatory compatibility to reduce burdens associated with unnecessary differences in regulations and standards” including “a mechanism to remove expeditiously unwarranted barriers that block the export of US food and agricultural products”.

In other words, more stringent consumer protections are an intolerable burden on the profit margins of multi-billion dollar US companies desperate to pry open new markets. The draft agreements promise Investor State Dispute Settlement courts, mechanisms built into many free trade agreements which essentially ensure a company’s right to profit against any potential future legislation threatening to even meagrely chip it away. They allow private companies to sue governments for loss of profit for things like environmental regulations and minimum wage guarantees; the Canadian government has been successfully sued for millions of dollars after they tried to ban a dangerous neurotoxin. The point is to bake government inaction into the firmament of domestic law.

At first, Boris Johnson’s government promised to guarantee food safety standards to quell troublesome rumours about chlorinated chicken and pesticide vegetables. Unsurprisingly, those promises have been smartly rolled back, starting with a recent agriculture bill causing uproar both within the sector and from devolved governments in Scotland and Wales threatening a direct revolt. Chief architects of the UK’s Brexit stance (Liam Fox prime amongst them) have clung doggedly to free-market fundamentalism which sees most checks and balances on business power as intolerable muzzles to the all-salvational power of innovation.

Unwilling to broker harmonisation with EU law, with few other replacement trade deals in the mix, a wounded UK economy nearing the brink of no-deal has little standing in negotiation to refuse the tainted offers of US negotiators. For the disaster-fantasists of the European Research Group (ERG), a structural weakness is a tactical advantage for the vulture forces of transnational capital straining at the regulatory bit. They can plead helplessness in a crisis of their own devising.

Free trade partisans have argued that the free market will take care of it, since companies must know that if they dole-out side helpings of salmonella, that may well hurt their businesses. Those arguments might make a little more sense if people were able to casually opt-out of buying food to survive from industries where generalised deregulation gives low-earners the choice between different flavours of campylobacter.

Those arguments don’t take into account the long-term negative health consequences of high-level pesticides and toxins in the food and water supply, or environmental impacts not traceable to one particular purchase that can be hauled in front of a civil court.

But the free trade absolutists know all this. They are in the business of freeing megacorporations from the consequences of their actions, and leaving everyone else out to dry.

Perhaps we should not then be surprised that the anti-red tape rallying cry is and remains a favoured agitprop tactic of ERG shysters and free-trade snake oil conglomerates, attempting to disguise a disaster capitalist power-grab as a populist revolt against sneering, censorious elites. It wasn’t just spin. It was a mandate. It was a promise.

Eleanor Penny is a writer and a regular contributor to Novara Media.

This article is the sixth instalment in her series on the political economy of things we consider to be waste, rubbish, junk – or filth.

Part one is here: Trans Bathroom Panics May Be New, but Public Toilets Have Always Been a Political Battleground

Part two is here: Racist Scaremongering Around Covid-19 Is Nothing New. We Have Always Blamed Racial Others for Disease

Part three is here: Space Junk Is Always Somebody Else’s Problem – But Eventually Someone Is Going to Have to Clean It Up

Part four is here: Coronavirus Has Shown That Cleaners Are Essential, but Labelling Them ‘Low-Skilled’ Legitimises Exploitation

Part five is here: Disease, Drugs or Looting – Brutal Policing is Always Framed As Protecting ‘the Public’ From Infection