You Can Have Schooling or You Can Have Policing. You Can’t Have Both

One provides care, the other destroys it.

by Khadijah Anabah

29 March 2022

The public was recently made aware of the case of Child Q. Her ordeal occurred in 2020 when Child Q was completing a mock exam. One of the invigilators claimed to have smelled cannabis on Child Q; teachers called the police, who subjected this young Black girl to an invasive strip search without parental permission or a chaperone.

Adultification, racism and sexism colluded to produce this harrowing incident, yet it was not isolated: 25 other children in Hackney were subject to similar searches in the same year, a fraction of the 2,014 strip searches performed on minors in custody in 2020.

Given this dire picture, calls for resignation – such as that made by Hackney mayor Philip Glanville to the principal of Child Q’s school – are not enough. We need to abolish the police.

Symbolic gestures like resignation seek to appease our outrage but do little to challenge the systematic abuse of young people at the hands of their nominal guardians. In such a system, it is not individual staff members that are to blame, but the entire rotten system. Schools are supposed to be refuges, spaces that free young people to make mistakes, develop their interests and imagine their futures – yet in recent years, they have become infected with the logic of policing.

From the asbos introduced by New Labour to the closure of youth clubs under Tory austerity, the space for young people to engage meaningfully with their communities is shrinking. Meanwhile, policies that demonise and even criminalise young people have proliferated.

Schools have been at the epicentre of this shift, as the racially-coded language of “inner-city schools” as well as racist myths of Black gangsters and brown terrorists are used to justify the surveillance of children. More so than any educational policy, the Prevent strategy has normalised the perception of children as young as four as an affront to white Britain. Children with cultures, values, and skin colours outside this hegemony are viewed as threats to national sensibilities and eligible for surveillance. Meanwhile, racist technologies of hyper-surveillance that see Black boys stopped ten times more than their white counterparts are imported into schools wholesale.

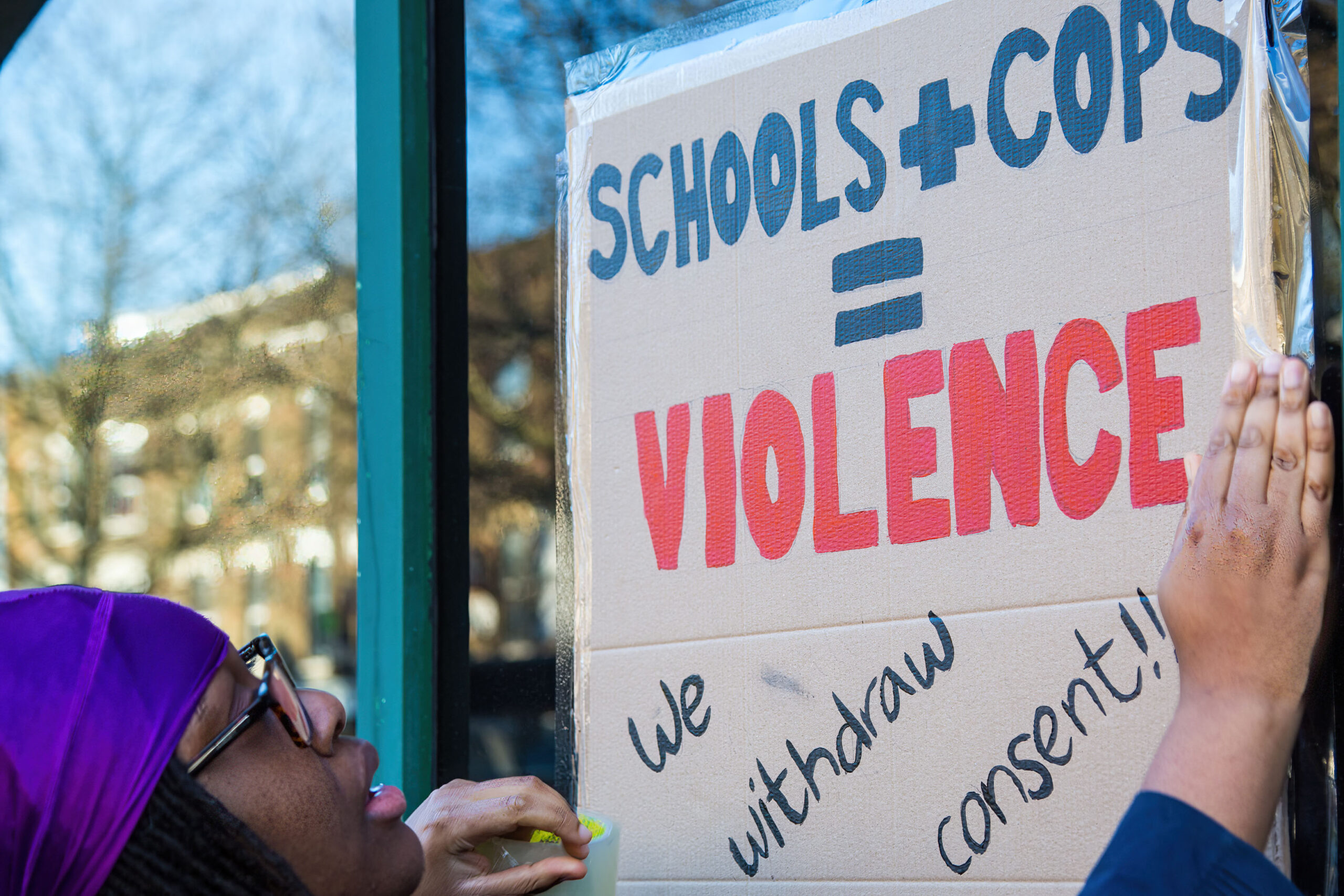

The normalisation of policing in educational institutions has sought to induct young people into a culture where their agency is continuously under threat. Despite this, young people are showing increasing resilience and resistance. Over the last few years, young people have been at the forefront of political movements such as Black Lives Matter and Kill The Bill. In response to the brutal treatment of Child Q, young people across the country have staged walkouts and sit-ins, calling for an end to the carceral systems that abuse them.

Protest at the petchey academy for justice for child Q pic.twitter.com/Pleq6U9wGe

— Justice for child q (@Justiceforchi12) March 18, 2022

Riding the wave of outrage prompted by Child Q’s case, hundreds of students at City and Islington College protested their treatment as criminals. In February, the college introduced handheld metal detectors operated by staff at their entrance, citing knife crime among students. In protest, the students argued that to be selected for a search prior to entering the classroom shames students by assuming their criminality and subjecting them to breaches of their bodily autonomy dampens their ability to be present in their learning. For these students, the use of searches ruins their educational experience. A plethora of abolitionist organisations are backing them up.

“Stop searching minors” – Students at City & Islington College have staged a walk-out in protest at their college’s ‘stop and search’ policy pic.twitter.com/oXU5TF71Ii

— Anna Lamche (@annalamche) March 21, 2022

The work currently being done by activists in Kids of Colour and No More Exclusions has for years campaigned for the abolition of police in schools and for a politics of care that understands the intersectional vulnerabilities of Black children especially. These organisers are guided by abolitionist principles, which call for an understanding of police, not as a treatment but as part of the infestation that enables and legitimises institutionalised violence against children.

For Kids of Colour and their No Police in Schools campaign, there is a contradiction at the heart of policing within educational settings. Through close work with young people, they make evident the disruptions and fear police presence has on the learning, especially Black children who already suffer poor educational outcomes due to institutionalised racism in schools; No More Exclusions has done ample work to highlight the disciplinary practices that see Black students overrepresented in suspensions and exclusions – something the organisation argues disrupts education and the development necessary to adult success.

Both these organisations make clear to us that education and the learning necessary to develop the full potential of young people is made impossible by policing and surveillance in schools. Knowledge building can only truly happen in a space of care, where students are trusted and empowered. Policing exists to stifle such development and forecloses students’ thriving.

Motherhood more so than anything is what guides my politics and my concern for children. But even more so as a mother of a little girl my anxiety is high. Reading child Q’s case was harrowing as someone whose been on the receiving end of police violence whilst I was in school.

— deej (@fanoniscanon) March 17, 2022

To genuinely care for young people, we need to ensure they have places that nurture them. Policing is diametrically opposed to care – and by continuing to insist on its presence in schools, we are failing children. In a society in which young people’s political agency is actively suppressed, we must stand alongside them, amplifying their voices and advocating on their behalf.

Khadijah Anabah is a psychology lecturer and researcher whose work explores Black students’ academic experiences and carceral systems in education.