The New ‘Accidental Death of an Anarchist’ Doesn’t Just Preach to the Converted

Typical theatre-goers can’t always be relied on to criticise the cops.

by Juliet Jacques

9 August 2023

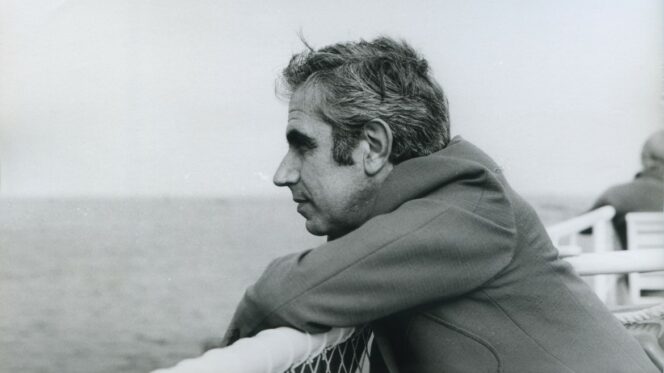

Dario Fo’s Accidental Death of an Anarchist is unmistakably a product of Italy’s politically turbulent ‘years of lead’, and yet it is frequently revised and revived all over the world. The play was written in response to the neo-fascist bombing of the National Agricultural Bank HQ at Piazza Fontana, Milan in December 1969, which killed 17 people and injured 88, and the death of anarchist railway worker Giuseppe Pinelli, who fell from a fourth-floor window of a police station during an interrogation after the authorities attributed the bombing to the far left. Fo’s farce premiered less than a year after Pinelli’s death and has since been performed across the world, helping him win the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1997. Most recently, it has returned to the stage in the UK in a new adaptation by Tom Basden at London’s Lyric Hammersmith and then at The Crucible in Sheffield, and then back to the capital for a high-profile run at the Theatre Royal Haymarket.

The play, in which a ‘Maniac’ infiltrates a police station, poses as a judge and, by pretending to be on their side, gets the cops to lay out their lies, petrified the Italian authorities. The police brought numerous prosecutions against Fo and his creative partner Franca Rame, and arrested them both before a performance of the play in Sardinia, leading the audience to stage an impromptu protest. It has been popular in the UK too, playing in the West End for several years as Margaret Thatcher came to power, with a madcap Channel 4 production in 1983, both from Gavin Richards’ script. Then, the events it depicted were recent enough to remain in the memory, with the deaths of Blair Peach and Colin Roach at the hands of the Metropolitan police brought up to emphasise its relevance to the UK.

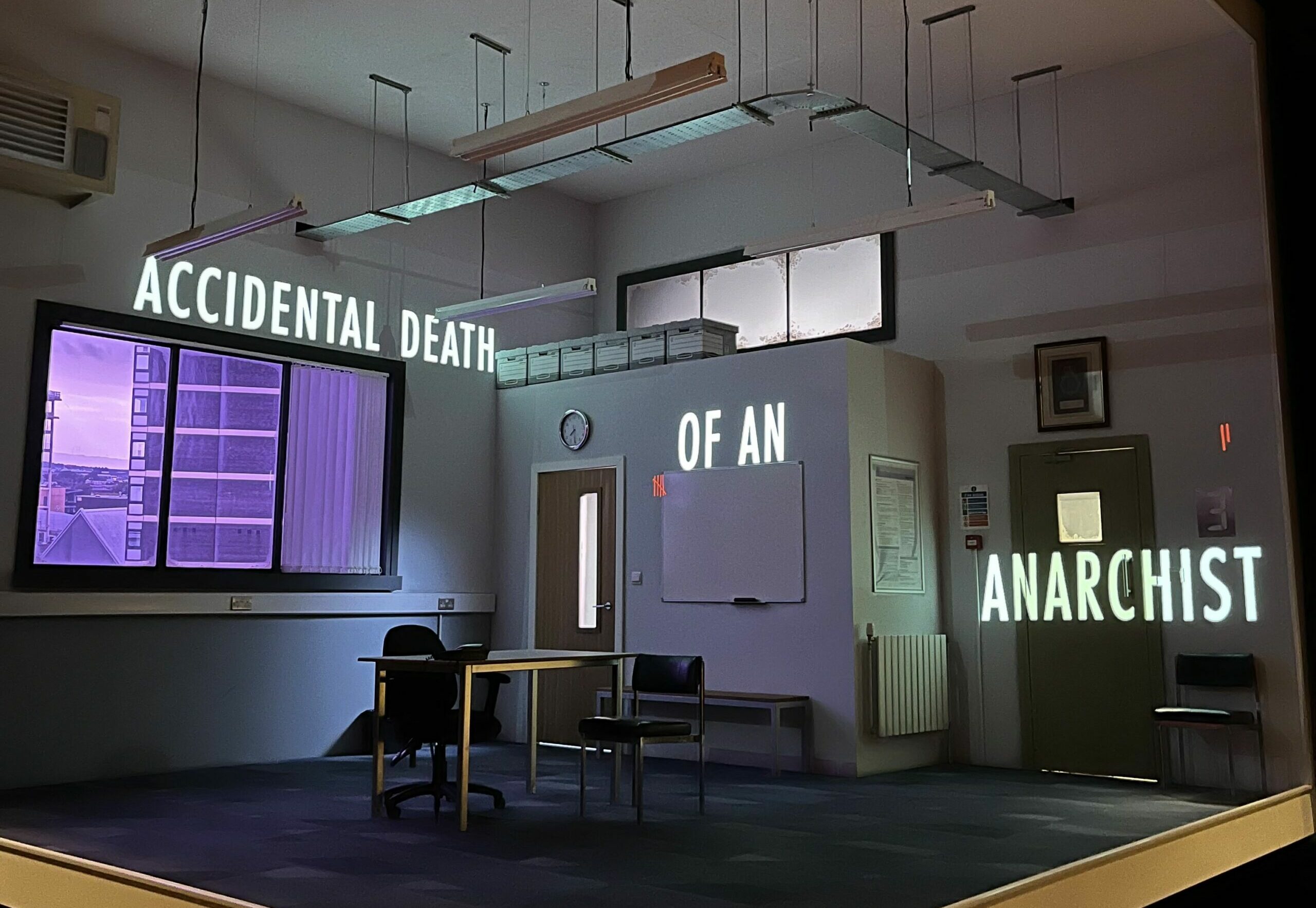

Daniel Raggett’s new production answers the questions of “why here and why now” relentlessly, referencing the Public Order Act and the killing of Sarah Everard in transposing the play to London in the 2020s. There are numerous other contemporary flourishes, as the Maniac, played brilliantly by Daniel Rigby, frenetically mentions everything from Elon Musk to diversity and inclusion training. The fourth wall not so much broken as never built – the Maniac is in constant dialogue with the audience, and in reminding them that they’re watching a morality play (in “the Queen Mother’s favourite theatre”, no less) goes so far as to discuss Fo’s funeral in 2016, where the crowd, like the Maniac and the police here, sang the anti-fascist anthem Bella Ciao.

In keeping the premise of an anarchist being accused of a bombing and then defenestrated, it seems a little anachronistic – ‘anarchists’ in the UK haven’t been much involved in bombing campaigns since the Angry Brigade of the 1970s. They are not mentioned here, and nor is the homeless man who died in an apparent suicide at the notorious Stoke Newington police station in November 2022. However, the Special Demonstration Squad of undercover cops, who infiltrated activist movements and committed all sort of crimes, are: making all this so explicit means that at times, it’s quite heavy-handed, in Basden’s version as in Richards’, but it’s so unrelentingly funny that it just pulls it off. (Indeed, I missed a few jokes because the audience were laughing so hard at the ones before.) Basden’s dialogue acknowledges that the message of Fo’s play will remain relevant because “this keeps happening”, and at the end, Anna Reid’s set turns into a cell, with a projection stating there have been 1,863 deaths in custody or after contact with the police in the UK since 1990.

The kind of reaction you would expect from rightwing critics is that this production, staged at a prestigious venue in central London, is preaching to the converted. In plenty of cases, that’s probably true. But firstly, there were plenty of younger people on the night I attended, for whom Accidental Death of an Anarchist may well have provided a fun and memorable piece of consciousness-raising. Secondly, despite what the Daily Mail or GB News might think, the type of white bourgeois left-liberals who make up a sizable chunk of its audience can’t always be relied upon to criticise the police. With commissioner Cressida Dick standing down after a series of scandals, including the organisation’s employment of officers arrested for rape, trust in the Metropolitan police is at a historic low – worse even than after the execution of Jean Charles de Menezes at Stockwell station in July 2005, the killing of Mark Duggan in 2011 (investigated by art collective Forensic Architecture) or the ‘accidental death’ of Rashan Charles in Hackney six years later. Unsurprisingly, faith is lowest amongst young people and particularly ethnic minorities, disproportionately targeted for stop and search as well as making up a large number of the deaths referenced at the end of Raggett’s play.

I don’t want to judge Accidental Death of an Anarchist on a purely instrumental basis: for it to connect with anyone, and especially to reach beyond the types of audiences associated with contemporary theatre, it must succeed on its own aesthetic terms. Fortunately, I think it does, with Basden’s humorous script and Rigby’s energetic performance lifting it (if only just, at times) above being dogmatic. But to dig further into that idea of ‘preaching to the converted’ – firstly, it’s important to note that this production is responding in part to the Everard murder, the draconian policing of the protests following it, and the ongoing criminalisation of protest as material conditions continue to deteriorate. The increased middle-class interest in critiques of the police comes out of the police’s institutional behaviours targeting the middle-class more – so a play that capitalises on that interest to highlight the ways in which those behaviours have been honed on Black and Asian people, teenagers and the left might strengthen the conviction of anyone who has only recently begun to engage with such critiques.

Secondly, it’s worth noting that the right never criticises rightwing creative artists for ‘preaching to the converted’ – only those to their left. (Indeed, quite the opposite is true: witness the endless shrieking about ‘rightwing comedians’ not being given a voice, a subset of their disingenuous whining about freedom of speech in every major newspaper, every day.) Culture is a good and useful way to convert: my own path to the left, as a teenager in a small suburban town, away from centres of political organising, was through reading novels, poetry and scripts, watching films, listening to music, and getting into comedy, all by left-leaning artists with strong social criticism, which led me onto theory and into activism. It’s not that the right don’t want leftwing artists to ‘preach to the converted’, it’s that they don’t want leftwing artists to preach or convert anyone – hence the constant Tory cuts to arts funding and assaults on arts and humanities degrees. It’s vital for us not just to ignore them, but to defy them, in any ways we can – and reviving the work of an artist like Dario Fo is as good a way as any.

Juliet Jacques is a writer, filmmaker, broadcaster and academic.